Vitrine of Dust

The bookshelf in my lounge room is dusty. The colors and edges of the books are dulled by the indistinct blur of uncertain matter. At first it seems inconspicuous, almost not there, but when I wipe my finger across the ledge I draw a line through it and a soft gray film gathers on my fingertip. When we think about dust if we think about it at all it is mostly a banal nuisance. It builds up in unreachable corners, under beds, on top of cupboards, and deep in the piles of carpets, couches, and curtains. We seek to banish it from our homes, wiping, beating, mopping, and vacuuming it up and then promptly disposing of this worthless material. And yet, as we unknowingly shed skin and hair and as the imperceptible abrasion of our lives in motion microscopically causes our homes to disintegrate, in just a few hours, dust persistently returns.

Our everyday experience of ordinary house dust may be one of mindless domestic repetition. VITRINE OF DUST is a guided tour that will, however, introduce you to some of the material and poetic wonders of dust, by referring to artworks and artifacts in the Eskanazi Art Museum'scollection.

FIRST FLOOR

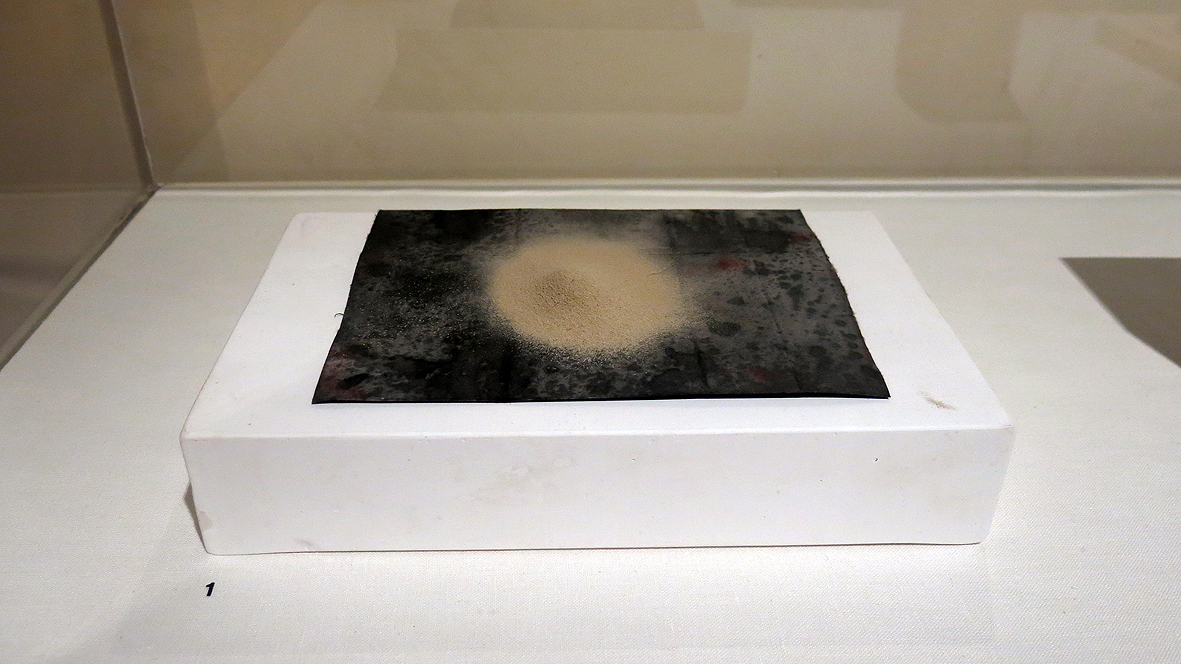

1. Vanitas, 1672

Juan Francisco Carrion

The vanitas genre of painting uses objects to remind us of the passing of time and of our own mortality. In the phrase “ashes to ashes, dust to dust” we can see that dust also reminds us of our own mortality. There is a kind of melancholy in knowing that we will eventually become dust. But another perspective is this… dust is also a shared materiality during our lifetimes. We unconsciously breathe it into our lungs and at the same time, as we shed skin cells and hair, our bodies’ manufacture it. There is continuity between dust and us—it does not just represent the end of our lives but is also imperceptibly present with us in our everyday existence. Rather then think of ourselves simply as eventually returning to dust, perhaps we might consider ourselves as always participating in the life cycle of dust.

2. Mountain View (In the Catskills), 1860

Charles Herbert Morre

The origins of dust are many. One significant contributor is nature. With the exception of bushfires and volcanic eruptions, which quickly throw clouds of ash particles into the sky and across the land, nature’s generation of dust usually occurs at glacial speeds. It is generated over eons by the forces of wind, water, and ice wearing away at coastlines, riverbeds, and mountain ranges. Heat from the sun also plays its part, evaporating moisture from the earth, turning topsoil into dry dust, and raising up salty airborne particles from bodies of water. Dust found deep in the cosmos is created over long periods of time. Stars and planets come into being from the gathering of gasses and dust and are consumed and diminished by the same thing. Did you know that space dust is still being caught in the Earth’s gravitational field? Every day more than a hundred tons of space dust falls on our planet. The dust that lands on your window sill could very well contain the remains of comets, meteorites, or burned-out stars from a timebefore the Earth was formed.

3. Marcel Duchamp

Whilst dust has existed in the universe since the beginning of time, its appearance in art only occurred in the last 100 years. Marcel Duchampis well regard for his Readymades, but he also used found objects in his collaborative work with Man Ray. During the construction of The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915–23), Duchamp allowed the pane of glass to gather dust for a year. After it had accrued a thick furry layer, Man Ray photographed the piece and titled it Dust Breeding (1920). The glass was then wiped clean except for one section, where dust was fixed to the glass with varnish. Since this work was produced, a handful of other artists have found different ways to work with dust.

SECOND FLOOR

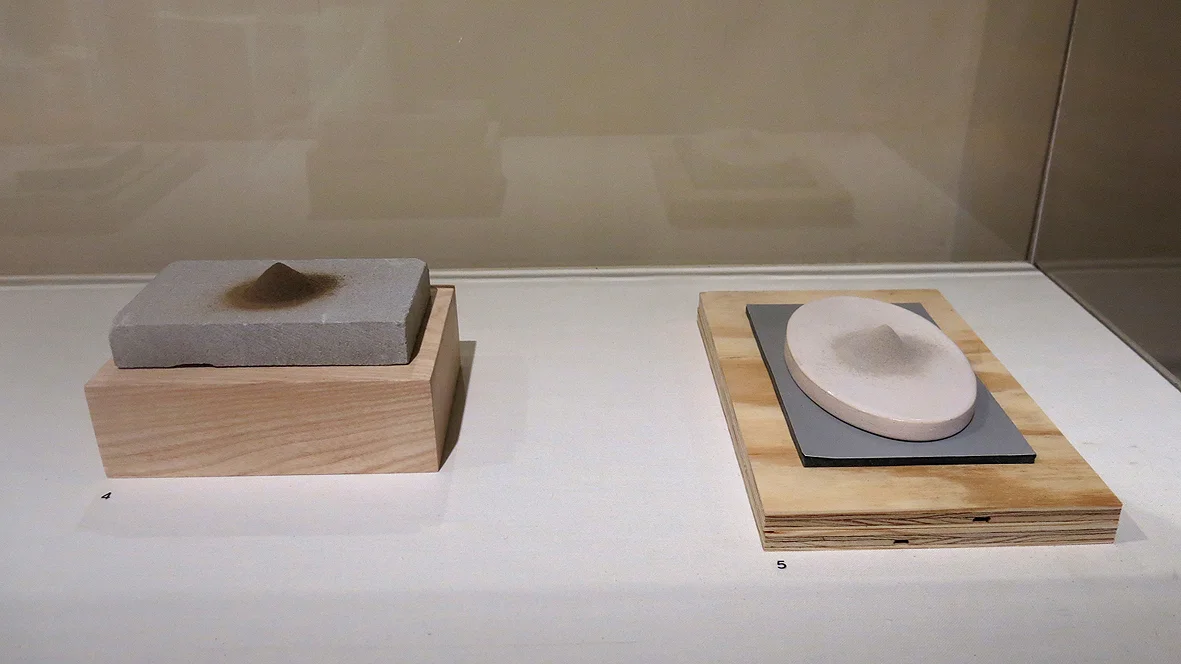

4. Long Spouted Vessel

Luristan

A curious thing about dust is that for a time it was related to the moral character of women. In the Victoria era the obsession with cleanliness was partly driven by the idea that a clean house reflected a pure soul. During this period dust was described as “Beggar’s Velvet” and “Slut’s Wool.” We may be less inclined to believe this now, and yet we persistently seek to remove dust from our homes. Why? Perhaps dusting performs the illusion of timelessness. That is, a dust-free home reflects a presence in which nothing changes. In seeking to control this substance, we may be projecting a deeper desire to control our lives. In preserving the appearance of order we can pretend that we are not affected by the chaotic state of flux that is life.

5. Ox and Cart

Han Dynasty

Humanity’s creation of dust is dramatic. Some places where dust production occurs are easy to call to mind. Think of how we toil on the Earth and mine its resources, or a construction or demolition site, or the billowing clouds of industrial manufacturing. The by-product of these actions is piles of dust accumulation. What is less visible, is the dust produced from the to and fro of traffic, and the wear and tear of objects in our daily lives. As we transport ourselves and goods—to the corner shop or all the way to the other side of the globe—the abrasion of tires on roads, trains on tracks, and people walking down the street causes microscopic erosions that scatter tons of dry pulverised matter into the world. Through the repetition of touch, we also cause imperceptible friction that wears away things. Over the course of our lifetimes, the act of making, moving, and using things leaves a dusty trail of disintegration behind us.

THIRD FLOOR

6. Barkcloth, Tapa

Samoa Island

This bark cloth shows a variety of repeated patterns. Shaping and ordering matter into form is at the core of many creative works. Dust, however, moves between form and formlessness. When it comes to rest in our homes it can accumulate over an object, adopting the shape of that object like a second skin. Settling on a flat surface, it can also mimic the shape of the surface upon which it lands as well as the form of an object recently removed. But dust is primarily an airborne material, carried on the wind and moving from place to place. When we catch it dancing in a shaft of sunlight, its loose, shifting shape is borderless and formless. That dust is void of specific form and yet is not purely formless is another reason for thinking of it as a unique material in the world.

7. Male Figure

Dogan people, Mali

The airborne nature of dust is important because it helps us understand how it contributes to the circularity of life and death. You may be aware that dust is the cause of diseases such as lung cancer, or that the smoggy pollution from manufacturing has a negative effect on the Earth’s atmosphere. But did you know that dust also assists in creating life? Here is an example.

Millions of years ago, dust storms from the Sahara Desert blew all the way across the Atlantic Ocean, settling on exposed coral reefs in the Caribbean Sea. These dust deposits contained organic matter that began to fertilize the exposed coral reefs, providing soil in which plants could grow. From the dunes of the Sahara Desert, via the migration of dust, came the inception of the lush tropical islands that we know today as the Caribbean Islands. Scientists now believe that the “raining down” of various desert dusts provided important nutrients to the Amazon basin, the Great Plains of North America, and Northern China.